Welcome to poison city.

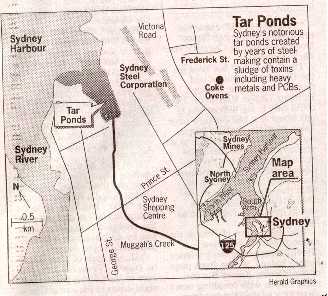

It was more than 10 years ago when Ottawa promised to clean up the Sydney tar ponds, twin lagoons of toxic goo and raw sewage that are the legacy of a century of steel making. Today, despite $60 million in taxpayers' money, repeated promises from federal and provincial politicians and the best efforts of dozens of local volunteers, almost nothing has been done.

Elizabeth May, executive diretor of the Sierra Club of Canada, calls Sydney the "worst toxic site in North America," pointing out that the tar ponds alone have 20 times more toxic sludge than New York's Love Canal.

The truth is that it is impossible to tell what the worst site in North America, or even Canada is, because no one has ranked the disasters left behind by the industrial revolution.

But Sydney is surely near the top of the list.

"This would never have happened in Toronto or Halifax," says May. "People simply would not have allowed it."

The tar ponds stink. They harbour more than 700,000 tonnes of hazardous waste, including 40,000 tones of PCBs that dribble to the sea with each turning tide.

Upstream, no one knows what toxic soup is brewing beneath an abandoned coal processing plant where 160 kilometers of underground pipe once carried some of the most deadly chemicals known to man. The soil regularly erupts in unnatural flames that simply can't be quenched.

Above the coal plant, just beyond a bright yellow hill of pure sulphur, is a century-old dump, a 76-metre-high mound of garbage topped by an aging incinerator that spews deadly mercury from its stack. A stream the color of orange day-glo paint runs through it.

The entire stinking mess is bordered by homes, ball fields, playgrounds, schools, supermarkets and even restaurants. last week, tests confirmed what some residents have long suspected: The deadly goo has invaded their lawns, a brook where children play and even the groundwater beneath their streets.

"We are amazed that people aren't marching on Parliament Hill about this," says Germain LeMoine, who works for the local committee charged with the clean-up.

"It is a gross, terrible mess. Sometimes we are all overwhelmed by what a mess it is, particularly by how much is still unknown."

It wasn't long ago that workers sneaked home jars of thick black oil from burned-out power transformers for older relatives who swore it cured arthritis. Today the oil isknown as PCBs, a substance banned because it causes cancer. The very tar that sits in the bottom of the fetid ponds was once chewed by workers to whiten their teeth. And the clear solvent that many spirited out to clean their car engines is listed as one of the most dangerous carcinogens on the planet.

Fred Tighe moved to a small bungalow overlooking the tar ponds two years ago. He says he doesn't worry about the pollution, even though he has to close his windows tight against the stench on hot summer days.

His dog, Barney, heads for the tar ponds whenever he gets loose. (There are no fences around the two lagoons, no signs to warn of the tonnes of toxic sludge and raw sewage).

Tighe says he came home one night and Barney was glowing in the dark. At first, one assumes it's a joke, a local tale spun for an out-of-towner, but Tighe is serious, though not alarmed.

"I came in the kitchen and it was dark and there was this thing - well, I couldn't tell it was Barney - this thing just glowing in the corner, kind of yellow like, a big lump glowing.

"I turned on the light, there was Barney, all covered in black tarry stuff, but there was this yellow skin-like thing on him, too."

Tigh scrubbed Barney with Avon bubble bath and the glow disappeared. he still isn't worried about the pollution.

"if it's going to get you, it's going to get you wherever you are," he says.

"We're still dealing with a community in denial," says Mike Britten, program co-ordinator for the action committee.

"Many people around here think we're nuts. if you put the (coal processing plant) back there in the same exact conditions, you would have people lined up from here to the causeway wanting to work."

Until recently, even the thick orange smoke that belched from the plant's blast furnace was considered a good thing.

"No smoke, no baloney," is what they still say in Sydney.

"If no smoke was coming out of stacks, your father didn't get a shift and you didn't eat," Britten explains. "To support our families, and support ourselves, we will do anything. That's reality."

The reality here is that for most of this century, the steel plant was just about the only game in touwn. Either you worked for the Sydney Steel Corp., a company that depended on the dollars generated by the plant, or you didn't work at all.

Air pollution controls that were required virtually everywhere else in Canada were never implemented in Sydney. The exemption was just one of many ways in which successive governments have tried to prop up an obsolete and inefficient steel maker.

Even today, about 600 workers manufacture heavily subsidized train rails and pig iron, although electric-arc furnaces replaced the coal-fired blast furnaces about 10 years ago.

One federal study showed that air pollution in Sydney was twice as bad as in Hamilton, even though the coal processing operation was much smaller.

"I can remember fighting with my father," says Eric Brophy, 65. "He

said, 'Don't worry about the smoke coming out of those stacks,' but it's

my generation that's paying the price for his job."

"I can remember fighting with my father," says Eric Brophy, 65. "He

said, 'Don't worry about the smoke coming out of those stacks,' but it's

my generation that's paying the price for his job."

Brophy's wife died of cancer, one of the thousands of local residents that make this island's cancer rate so remarkable.

Nova Scotia has the highest cancer rate in Canada. But within Nova Scotia, Cape Breton tops the charts. It has the highest rates of lung cancer, breast cancer and stomach cancer in the province. Sydney residents also have higher rates of lung disease and heart disease.

Peggy Burt, 60, is Brophy's fiancee. The lifelong friends are to wed next month.

Burt is not well. She was diagnosed with cervical cancer at age 37 and now suffers from an array of medical problems that prevent her from taking a simple stroll down the street.

Almost all the women in her family have had some form of cancer, and so have many of the men. Burt knows that cancer has a genetic link, but she wonders why so many of her friends and neighbours are also ill. Five of the 20 girls from her Grade 8 class at Sydney's Holy Redeemer Convent have died of cancer.

"The people I grew up with, my school chums, they aren't here any more," she says.

Driving down the street where Burt and Brophy grew up, there are only two houses in two blocks where they don't know someone who has had cancer. Both blame pollution in the air, the water and even in the vegetables from the gardens of their childhood.

"I can remember coming back from picking blueberries as a little girl and my father saying, 'Don't look up,' because of the stuff falling out of the sky. There was orange dust everywhere. You could feel it pricking your skin," Burt says.

Brophy left Sydney to enlist in the military and spent most of his adult life away. Many of the people working hardest to clean up this city have moved here from elsewhere, or have spent a long time away before returning home.

Doug MacKinlay, a volunteer with the clean-up committee, does not think that's a coincidence.

"This is a nexus between class and ecology," says the lawyer and Nova Scotia native.

"We are a have-not part of a have-not province," MacKinlay says. "Powerlessness is one of the biggest obstacles here. A lot of people here feel marginalized. Citizens are used to having their needs shunted aside. They have come to expect it and somewhat accept it."

Larissa Boone was a healthy little girl until she moved into a purple clapboard

home beside the old coal processing plant. Now the rambunctious toddler

squirms beneath a plastic respirator tied to a whirring machine that sprays

medicine into her ailing lungs.

Larissa Boone was a healthy little girl until she moved into a purple clapboard

home beside the old coal processing plant. Now the rambunctious toddler

squirms beneath a plastic respirator tied to a whirring machine that sprays

medicine into her ailing lungs.

In the five months since Larissa and her mother Tanya moved to Frederick Street., the 2-year-old has been plagued with problems; a right eye recently swollen shut with pus, a recurrent ear infection and now, fluid in her lungs that won't go away.

Larissa loves to play in the yard, to pick up bits of coal and slag and toss them toward the orange creek, but whenever her mother lets her out, she gets a nasty rash.

"I think it might be connected to the pollution problems, but I don't know," Boone says of her daughter's perplexing new health woes.

"Nobody came by. Nobody has told us anything. Wouldn't they say something if it wasn't safe here?"

Not necessarily. Both politicians and health officials have played down the concerns of residents of Frederick St., where testing has found arsenic levels 13 times higher than federal guidelines, as well as an array of other dangerous chemicals.

The local MLA publicly scoffed at a constituent who complained about the contamination, saying she would have to eat the arsenic to be harmed.

Officials rushed to correct him the next day, pointing out arsenic can be absorbed through the skin and even become airborne.

Nova Scotia medical officer of health Jeff Scott suggested at one public meeting that the federal guidelines were too strict and said the tests revealed no immediate health hazard to residents.

Those tests showed that a brook and backyard soil from Frederick St. contain arsenic, molybdenum, benzopyrene, antimony, naphthalene, lead and copper, all at concentrations many times above federal guidelines. Those chemicals are known to cause various cancers, birth defects, heart disease, kidney disease, brain damage, immune deficiencies and skin rashes.

As far as Boone knows, no one has tested her soil or the brook that runs behind her yard, even though the highest arsenic levels were found in the yard of her next-door neighbour. No one has offered to check if Larissa is accumulating poison in her system.

health officials say it's almost impossible to find a direct link between the toxic contamination and health problems.

"You're never going to find a smoking gun," says Don Ferguson, a scientist with Health Canada who is involved in studies of the area.

He, too, does not believe people on Frederick St. are in immediate danger. While he admits the coal processing site adjacent to Frederick St. is a hazard for those who actually walk across it, he said the toxic fumes can't travel as far as people's homes.

"Where are the residents getting it from? It's not in the air, not in the (drinking) water and they aren't rolling in it. There is no pathway."

But that doesn't explain why almost every resident of Frederick St. has complained of sore throats, headaches and nausea since workers started digging up the nearby coal processing plant.

Boone's next-door neighbour, Debbie Ouelette, was actually relieved when recent testing showed arsenic levels 13 times higher than federal guidelines in the brook behind her house. "Now that there is proof of the contamination, they have to do something," she says.

But she wasn't surprised. Ouelette says she's never seen a frog in the creek, only dead birds. Mice in the neighbourhood are horribly deformed, she says. Some don't have tails and their ears look as if they have been turned inside out.

"They don't even look like mice. They are totally gross," Ouelette says.

Tomorrow:

Cleaning up

Tomorrow:

Cleaning up Contact

Sierra Club,

Contact

Sierra Club,