The Sydney Tar Ponds - Excerpts from news reports.

Note: The Sierra Club of Canada is not responsible for the content of the following reports nor affiliated with its authors.

Wednesday, December 11, 2002

Halifax Herald

Study suggests health threat from steel mills

By Lois Legge / Staff Reporter

A new study clearly shows the ailments of many Sydney residents can be linked to decades of steelmaking, says environmentalist Bruno Marcocchio.

“And it’s the clearest evidence yet of the need to implement a buffer zone before any (cleanup) work happens,” said Mr. Marcocchio, spokesman for the Sierra Club’s Atlantic chapter, which fears residents are still at risk from contaminants in soil and water related to steelmaking.

But Parker Donham, spokesman for the province’s Sydney Tar Ponds Agency, stressed the study focuses on air pollution from operating steel plants in the Hamilton, Ont., area.

The Sydney steel plant was closed in 2000 and its pollution-pumping coke ovens haven’t operated for almost 15 years.

Mr. Donham said Sydney’s air quality is just fine, even better than in Halifax or Toronto.

“And why wouldn’t it be? There’s no industry left here. I mean, call centres don’t pollute the air.”

The study was done by researchers with McMaster University and Health Canada in Hamilton, Canada’s steel capital.

It doesn’t address the Sydney situation, although lead author Christopher Somers said Tuesday that coke oven chemicals don’t have to be airborne to be harmful.

The study found genetic mutations in mice that had been placed downwind from steel plants.

Changes in the rodents’ DNA could make them and their offspring more prone to cancer and other diseases, found the researchers, who believe the mutations were caused by exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Hundreds of thousands of metric tonnes of cancer-causing PAHs, steelmaking byproducts that can end up in the air and also pollute soil and water, are in the Sydney tar ponds and have also flowed into Sydney Harbour.

Citizens and government officials differ on whether the chemicals have seeped onto residential properties.

“It’s not necessary for them to be breathed in, in order to have the same effect,” Mr. Somers, a PhD student at McMaster, said in an interview.

“It’s all about dose,” he said. “The way that our animals are getting dosed would be . . . through inhalation but you could certainly get them through ingestion . . . or if they are present in Sydney Harbour and people are eating fish that are coming out of there.”

People could also possibly breathe in some of the chemicals if the wind is blowing a certain way, he said.

“There are also what we call volatile PAHs that would evaporate off of those tar ponds.”

Sydney-area residents have long been concerned about the health effects of the 700,000 tonnes of toxic sludge in the tar ponds, the waste from a century of steelmaking, as well as the contaminated coke ovens site.

The coke ovens, which baked coal at high temperature for use in steelmaking, closed in 1988.

The Hamilton study also found mutations in mice sperm and that the offspring of mice placed a kilometre from steel mills had up to twice as many genetic mutations as mice raised at a farm 30 kilometres from Hamilton.

“It goes a long way to explaining our elevated rates of birth defects here,” as well as high rates of cancer and respiratory and auto-immune diseases, Mr. Marcocchio said of the study.

He said the research is all the more reason the province should expand the buffer zone around the contaminated sites when the long-awaited cleanup begins.

Mr. Donham said residents will have ample say in the cleanup through consultations planned by the Joint Action Group, the group of volunteers and government advisers in charge of the cleanup.

Monitoring stations in Sydney show air quality is fine and “the risk assessments that we’ve done on the tar ponds and the coke ovens have shown that these materials are not presently leaving the site,” said Mr. Donham.

But Mr. Marcocchio believes residents are still at risk.

He and others felt ill just while demonstrating at the edge of the tar ponds last summer, he said.

“It was a day when the wind was blowing across the ponds in our direction . . . and within five minutes, everyone was feeling very ill. . . . We all left with headaches and had trouble breathing.

“Breathing that stuff is still a problem. Just because the plant is no longer operating doesn’t mean we’re not being still exposed to those PAHs on an ongoing basis.”

Saturday, November 9, 2002

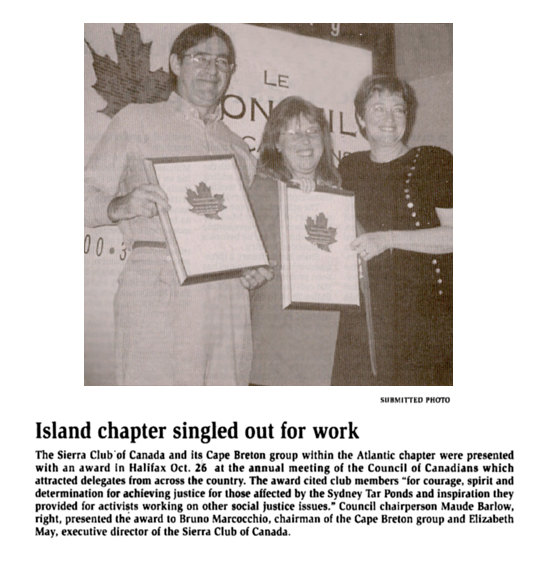

Cape Breton Post

Wednesday, October 23, 2002

Halifax Herald

Tar ponds action now,

watchdog says Ottawa’s commitment to cleanup shaky - environment commissioner

By Brian Underhill and Paul Schneidereit / Staff Reporters

The Chretien government’s continued financial commitment to cleaning up the toxic tar ponds in Sydney is far from certain, Canada’s environmental watchdog said Tuesday in Ottawa.

Calling the tar ponds one of Canada’s largest and most contaminated sites, Environment Commissioner Johanne Gelinas said the Joint Action Group is expected next April to recommend ways to handle the next stage of the cleanup.

But Ottawa’s role in co-operation with provincial and municipal governments is up in the air.

“Federal department officials informed us that the federal government has not yet decided on the extent of its future contribution, if any, for the costs associated with the next cleanup phase of the Sydney tar ponds site,” Ms. Gelinas said in a report tabled in the Commons.

Ms. Gelinas later told reporters that the time is over for talking about cleaning up thousands of toxic sites like the tar ponds.

“We have to go beyond dialogue now and act,” she said. “These problems are there, people are exposed to health risks, the environment is contaminated and we have to stop talking and move ahead with solutions.”

Elizabeth May, executive director of the Sierra Club of Canada, said Ottawa should be taking charge of the tar ponds cleanup.

“This report will be a shock for a number of people to realize that the federal government has not yet decided if any of its funds will go into the ultimate cleanup,” she said.

Environment Minister David Anderson said he lacks the means to spend billions of dollars on the Sydney tar ponds and thousands of other toxic sites across Canada.

“There’s no question the Department of Environment is not well funded,” he said. “We’re trying hard to make sure we do the very best job we can with limited funds.”

In the past 20 years, the federal government has spent over $250 million on the tar ponds site and nearby areas, the environment commissioner’s report says.

That includes more than $66 million on environmental studies and cleanup attempts since the 1980s and another $187 million on the modernization of steelmaking facilities in Sydney.

Federal officials said Tuesday that the government is expected to announce a toxic site cleanup fund in a few months.

Some sources said the fund could be as much as $2 billion, but it will be a national program and there will be no mention of individual projects.

The tar ponds could be excluded, since Ottawa does not consider them a federal toxic site, despite the money that’s been invested in the cleanup.

Ms. Gelinas said there is a lack of policy in areas of multiple jurisdiction, as in the Sydney case, and that the federal government must address the issue.

She said the amount of money Ottawa has put into the site is “not little” but is small potatoes compared to “the overall cost of billions of dollars that is needed to address the issue of contaminated sites in this country.”

Dan Fraser, chairman of the Joint Action Group, said he agrees that Ottawa should make a commitment to “the larger funding that’s required to carry on with the big cleanup.”

John Morgan, mayor of the Cape Breton Regional Municipality, said the report echoes his view that Ottawa has not revealed the costs or made a commitment to a final cleanup.

The bill for the final cleanup of the tar ponds and former coke ovens sites will depend on what technology is approved, but estimates have put the price tag at $500 million to $700 million.

Monday, October 14, 2002

Halifax Herald

Sydney resident urges relocation during cleanup

By Donna Anderson

Sydney - Cleanup work at a vacant lot in Whitney Pier last week has prompted renewed calls for relocation of residents during removal of contaminated soil from properties near the tar ponds.

Ann Ross of Laurier Street said last Thursday and Friday’s work at the lot, down the road from her home, shouldn’t have been done before families in a nearby apartment house were moved out.

“The stench of raw sewage was terrible,” said Ms. Ross, whose property is also slated for cleanup. “I have great concern for the young children that live only a foot from where this work is taking place.

“The hydrocarbons on that property are so high that they had to go down more than the regular two feet (0.6 metres).”

The lot, which used to have a house on it, is among properties on more than half a dozen streets targeted for cleanup after the provincial and federal governments released a soil study showing widespread contamination.

The contamination is blamed on waste generated by the former Sysco plant over more than a century of steelmaking.

Parker Donham, Sydney Tar Ponds Agency spokesman, confirmed testing indicated there were hydrocarbons in the soil.

“They dug deeper than they normally do, about six to eight feet (1.8 to 2.4 metres) because some type of oil was present in the soil, likely home heating oil,” he said.

“But the only hazard for residents was the physical hazard created Thursday night by the deep hole. A security guard was on site Thursday night, and the hole was filled in on Friday.”

Mr. Donham described the cleanup as routine.

“This was handled exactly as any oil spill is handled. We don’t evacuate people when oil is delivered to your home, and there was no reason for concern.”

Soil removed from the Laurier Street lot has gone to the landfill.

Wednesday, October 9, 2002

Halifax Herald

Cleanup proposals disappoint

By Bruno Marcocchio

IT IS VERY disappointing to see the list of seven proposed options for remediating the Sydney tar ponds and coke ovens site. Six years of the JAG process has resulted in offering variations of the two solutions already proposed and rejected by the community: incineration proposals and capping options. The only new options, using chemicals or detergents to make the chemicals less hazardous, are impractical and ineffective.

Incineration is not an acceptable option. The federal government has assured us that the remediation will, at minimum, meet the Canadian Council of Ministers of Environment guidelines. The CCME outlines that an incinerator must not be closer than 1,500 metres to homes. This rules out both incineration done onsite or at either power plant on the island. The 50,000 tons of PCB cannot be incinerated in an unlicensed facility and must not be ignored the way they were in the first failed attempt.

The capping proposals are merely a coverup, not a cleanup proposal. We as a community soundly rejected this in 1996. We know that capping will not stop pollutants from moving into the environment, and is cosmetic at best.

The promise of the JAG process was to find a solution in an open and transparent process. The seven proposals brought forward were done in the backrooms with no public input, exactly the same way as the two previous and failed attempts. There was absolutely no public discussion of how these solutions were decided upon or how others were ruled out.

The most safe, cost-effective and elegant technology, the Eco Logic reduction process, a technology that could deal with both the tar ponds and coke ovens site, was dismissed by the backroom consultants without a trial. Why?

This technology uses hydrogen to break down organic molecules into simple compounds like methane. It is a closed-loop system, which means there are virtually no emissions. It has regulatory approval and is being used to destroy chemical weapons, PCB, and other toxic wastes safely. It is small and can be moved to the various sites, simplifying the need to move the contaminants long distances. Why was so simple and safe a system ruled out?

JAG has publicly stated that it hopes to avoid a full panel review of the selected technology. Without a panel review, there will be no public hearings to ask these questions and explore better options. Public input and transparent decisions will be denied us as a community once again. Once again, patronage, not human health, will determine the outcome.

The Sierra Club thinks that people and human health must come first. A full panel review is the only way to have meaningful public input. JAG has broken every promise that was made to us as a community. For our children’s sake, we cannot allow backroom decisions to waste more money and another opportunity to do things right.

Bruno Marcocchio is chairman of the Sierra Club, Cape Breton.

September 14, 2002

The Toronto Star

Stink growing near Sydney pond

Residents denied toxic cleanup unless they waive litigation

WHAT THE federal and provincial governments are doing in Whitney Pier is just plain nuts.

Either officials are deliberately ignoring a serious health hazard facing hundreds of men, women and children, or they are wasting $2 million on a public relations exercise that is not making anyone feel better about anything.

You decide which.

Here are the facts:

- The governments are spending $2 million to clean up a few dozen homes and yards in one Sydney, N.S., neighbourhood near a defunct steel mill and toxic waste site.

- It is almost certain that many other homes in Whitney Pier are also contaminated, but officials have refused all further testing. Even where a home is surrounded by poisoned soil, the government won’t test or offer to clean it up.

- Officials have refused to test any homes in the other two neighbourhoods that surround the old steel mill site, even though private tests have found similar poisons in one of them.

- The governments have agreed to clean up 63 homes ÷ but only if residents sign away their right to sue if the job isn’t done right.

Sydney is the home of what Sierra Club of Canada president Elizabeth May calls the worst toxic waste site in Canada. It’s an impossible claim to verify, but the obvious truth is that the problem is very bad. The tar pond’s stinking waters shelter at least 40,000 tonnes of cancer-causing PCBs and all of Sydney’s raw sewage.

A field just above the pond is saturated with chemicals and metals like benzene, toluene, arsenic and lead. When an activist started shovelling the muck into barrels as a publicity stunt, one reporter covering the event passed out. Another threw up.

No one disputes the pond is unpleasant. What they do argue about is whether the stinking poisons hurt people. Sydney has some of the worst health statistics in Canada. Birth defects are high, lifespans are short. The rates of some cancers and other diseases lead the nation.

The official line has been that the pollution and the sickness are not related, that most of the problems can be explained away through local lifestyle issues connected to poverty, smoking and diet. That argument drives May crazy.

“It’s absurd that the government position is that whatever is wrong with this community is not related to the fact they are living in the midst of toxic waste,” she says.

Both provincial and federal officials have made key decisions in this mess. Working through a complex spider web of committees and consultants, the two levels of government are sharing the bill for the debacle, and calling the shots.

Four years ago, a mother living on Whitney Pier’s Frederick St. started to worry about the goo in her basement. The goo was tested. It turned out to be full of arsenic. Frederick St. residents kicked up a fuss and, with an election looming, the provincial government agreed to buy them out.

That started the neighbours wondering. People who had lived in the shadow of the steel plant for generations, people who had scoffed at the alarmed residents of Frederick St., now demanded their own properties be tested. The government did what governments do in a crisis ÷ it hired a consultant.

After the first tests came back, the Florida scientist hired to study Whitney Pier warned people not to let their children play outside until further study was completed. Empty lots where children had frolicked were fenced off with bright red plastic webbing because arsenic and lead were found in the soil.

Now residents were downright panicked, determined to get themselves and their children away from the poisons they suspected might be causing some of Sydney’s horrible health problems. When the government offered more testing, many refused, afraid that the government would use the results as an excuse not to move them.

In the end, the owners of only 124 properties agreed to the testing. When the tests were done, consultants recommended 88 properties be cleaned up, including 63 private homes.

Even then, there was a catch.

The authorities insisted property owners promise not to sue in connection with the cleanup.

The way the Rev. Vincent Waterman sees it, they want him to barter away the health of future children in exchange for his own peace of mind. Waterman doesn’t know the exact nature of the poison in the basement of his church rectory, but he knows it must be bad because government workers bolted a big steel plate over the mess and told him not to go near it.

He wants to sign the cleanup contract, but is afraid. What if they don’t get all the poison and a child ends up playing in that basement after he moves or dies? What if they find more toxins after the first cleanup is finished?

“It’s ludicrous to agree not to sue before the work has even begun,” he says.

“You don’t want a child in the future stuck because of a clause that an adult signed unwisely. I am truly caught between the devil and the deep blue sea. I wouldn’t want a dog to be in my predicament.”

In the meantime, the Sierra Club has launched its own testing, a dust survey to see if the poisons are migrating inside homes.

Parker Bars Donham is the government spokesperson for the project. He has already dismissed the Sierra Club study as “propaganda.”

When asked why the government is cleaning up the properties, Donham first cites “health concerns” identified by the consultants. But when asked why the government won’t test adjoining properties, if there are health concerns, he backtracks.

“Our conclusion is that there isn’t cause for alarm about people’s health,” he says.

So why are they spending $2 million to clean it up?

“As a matter of public health, we don’t think it’s absolutely necessary,” he says. “We are cleaning up to fulfill a political commitment to the people of this community.”

Maybe that is supposed to be reassuring, but somehow, it isn’t.

“I’m at an age when I will have to go under ground soon anyway,” says Waterman, who just turned 76.

“I’m left in limbo. I guess I must just live with this. I’m in more hot water than a tea bag.”

Monday, March 11, 2002

Halifax Herald

C.B. pollution standards spur demand for data

By Tera Camus / Cape Breton Bureau

Sydney - The Sierra Club of Canada demanded Friday that the federal government release all data that led to Ottawa creating a lower standard for cleanup for toxic land in Sydney than in other cities across Canada.

The environmental group says Health Canada is ignoring scientifically tested safe soil guidelines established by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Instead, the government is using land in North Sydney as a benchmark.

The CCME limit for arsenic in soil is 12 milligrams of arsenic per kilogram of dirt. The federal government's limit for Sydney is 72 mg/kg.

"It seems every time Health Canada finds high contamination levels on a property, they change the standard to make what was unacceptable yesterday, acceptable today," said Daniel Green, scientific adviser to the Sierra Club.

The federal Health Department refused last week to disclose results from tests taken last summer in Sydney. But spokesman Don Ferguson said most of the soil samples from Sydney fared better than those taken from North Sydney. He refused to how many soil samples tested below the lower CCME limits.

Thursday, March 7, 2002

Halifax Herald

Sydney soil tests find most homes safe

By Tera Camus / Cape Breton Bureau

Sydney - Government officials say that only one soil sample from among 333 tested last summer in Sydney and nearby communities showed an unsafe concentration of toxins.

Health Canada spokeswoman Tracy Taweel described the results as consistent with earlier health studies that declared the communities around the infamous tar ponds and coke ovens sites to be safe.

“There was nothing in there that gave cause for further alarm,” Ms. Taweel said. But Raylene Williams is far from convinced. Her Intercolonial Street property, on the shore of the tar ponds, tested cleaner than those in North Sydney, 10 kilometres away.

“Look, I’m confused, I’m really confused,” Ms. Williams said as she flipped through the pages of test results at her kitchen table, where the window overlooks the 700,000 tonnes of toxic goo in the tar ponds.

“This is tearing me apart, it’s taken over my life,” she said. “The government is, after lying to us so damn much. . . . I’m 60 years old right now and I feel that everything I’ve worked for is worthless. I can’t sell my property, I can’t enjoy my property.”

More worrisome now is the health of her grandchild, just over a year old. His mother has high levels of lead in her breast milk.

“There’s something wrong with his leg and it’s affecting his motor skills, and the doctors are blaming it on his mother’s milk,” Ms. Williams said.

Ms. Williams’ soil was tested for 49 chemicals, many of them known carcinogens or having the potential to impair bodily functions. Forty of the 49 were found to be less concentrated than in North Sydney properties but many were still well above national guidelines for safe soil established by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment.

Ms. Williams doesn’t believe the latest findings because they differ from those resulting from tests done at the Environmental Services Laboratory last summer through Mayor John Morgan’s office.

Those samples tested seven times above acceptable limits for arsenic and three times higher for lead, iron and manganese. The results issued Wednesday showed three times the acceptable level of arsenic, twice the acceptable level of lead and slightly more than the acceptable limit of iron.

In North Sydney, arsenic levels averaged 72 milligrams per kilogram of soil - the national guideline is 12 - while lead was twice as high as the acceptable limit of 140 mg/kg. Other chemicals among 90 samples taken from downtown North Sydney also exceeded national numbers.

Federal and provincial government officials refused Wednesday to disclose any of the concentration levels found in Sydney.

“We won’t do that,” said Don Ferguson, director general of Health Canada, saying it’s to protect the interests of property owners.

He said most soil samples taken in Sydney produced better test results than those in North Sydney but he refused to say how many were over the national guidelines for safe soil.

One property showed lead at more than 1,400 mg/kg. Mr. Ferguson refused to say where that property is but he said it will be investigated further.

He said government officials picked North Sydney for comparison testing because it is an urban area not believed to be affected by fallout from the government’s coking process at Sydney Steel that turned the sky orange with uncontrolled pollution for decades.

North Sydney is 10 kilometres downwind of Sydney. Nearby Sydney Mines also had a steel plant for years.

“There were no patterns,” Mr. Ferguson said of the results. “If there was a pattern, it was random (levels) were up and down.

“If we did the whole province of Nova Scotia, I don’t think we’d find anything different.”

He also reiterated that the federal and provincial governments will not clean up any property that tests similarly to North Sydney samples, even if it exceeds Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment values.

Contamination levels in North Sydney are considered naturally occurring, Mr. Ferguson said.

“You can’t beat Mom Nature,” he said. “You choose to live in an urban centre, you choose to live in those conditions.”

Many area residents have demanded to be moved at government expense and have said that national environmental standards should be applied to the area.

Friday, March 1, 2002

Halifax Herald

Studies numerous as the opinions

Sydney residents suffer higher rates of cancer and other illnesses. Is their environment to blame?

Photo caption (file): Elizabeth May, of the Sierra Club of Canada, went on a hunger strike on Parliament Hill in Ottawa last May to protest the government’s lack of action on Sydney’s toxic waste problem.

By Susan LeBlanc / Staff Reporter

OVER THE PAST 25 years, a number of major health studies have been done on the Sydney area:

March 1977: Health and Welfare Canada reports that the testing of hundreds of Sydney schoolchildren in 1976 found “a small but statistically significant connection” between their respiratory function and the level of air pollution in their neighbourhoods. But “there was no evidence that this resulted in disease as judged by ear, nose and throat examinations,” says the report. Sydney adults tested normally.

December 1985: Dr. Yang Mao of Health and Welfare Canada says death certificates from 1971 to 1983 show Sydney residents suffered “significantly elevated mortality” from cancer. Men aged 35 to 69 were especially prone to cancers of the stomach, digestive tract and lungs. Women died mostly from cancers of the stomach, breast, uterus and cervix.

The study also finds high death rates from circulatory diseases and, among men, deaths from respiratory illnesses, cirrhosis and pneumoconioses (lung diseases, including black lung). The report notes stomach cancer and some respiratory diseases have been linked generally to coal mining; lung cancer has been tied to coke oven workers.

“Effects (of related contaminants) to the general public at normal ambient air levels have not been demonstrated,” it says.

August 1998: Cantox Environmental of Halifax releases a study prepared for the provincial Health Department on the human health risk of the Frederick Street area in Sydney. (Residents had grown concerned when liquid oozed from a nearby rail bed and when coal cleanup at the nearby coke ovens site appeared to raise irritating dust.)

Researchers used a computer model to assess risk, combining data on area contaminants, their potential hazards and residents’ estimated daily exposure. Residents’ blood and hair samples were analysed, as were soil, drinking water from nine homes and root vegetables from local gardens.

While lifelong exposures to carcinogenic PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) were “slightly elevated,” overall “no measurable adverse health effects in local residents are predicted to result from long-term exposure to chemicals in the Frederick Street neighbourhood,” Cantox says.

September 1998: A report by Health Canada scientists Dr. Pierre Band and Dr. Michel Camus reveals Sydney residents have much higher death rates from 22 diseases than other Canadians do. Death by cancer is 16 per cent higher in Sydney, says the report, done for the Joint Action Group.

From 1951 to ‘94, residents’ lifespans were 10 years shorter than could be expected. Among the top killers: cancers of the esophagus, lung, stomach, breast, pancreas and bone marrow. Non-cancer killers included asthma, diabetes and multiple sclerosis. It’s suggested colon and breast cancer, plus male diabetes, get a further look.

October 1998: Dr. Judy Guernsey of Dalhousie University in Halifax and other researchers find Sydney-area men and women much more likely to develop cancer than other Nova Scotians. Females were 47 per cent more apt to get cancer in the period 1989-1995, while males were 45 per cent more likely.

“Women were at increased risk for cancers of the breast and cervix, and Sydney men were at increased risk for cancers of the colon and rectum and prostate, relative to N.S. women and men,” the researchers say. They also find that residents of other parts of Cape Breton County were more at risk, especially for cancers of the stomach, breast and cervix for women and stomach, lungs and prostate for men.

January 1999: A review of the 1998 Cantox study by Ontario researchers on behalf of the Sierra Club environmental group disputes Cantox’s claim that Frederick Street residents are not at risk. “We are unable to support (the conclusion) based on the meagre sampling data and the uncertainties contained in the methodologies employed,” the review says.

April 1999: Three Ontario doctors commissioned by Cancer Care Nova Scotia review the two 1998 studies and find no “specific cancer problem, but rather an overall health problem” in Cape Breton. The panel agrees with Health Canada that since the 1950s, Cape Bretoners have been more apt to die of cancer and other diseases than other Canadians have been. But the experts blame lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity, not the environment.

Fall 2001: An updated 1999 study by Dr. Linda Dodds of Dalhousie University says Sydney had a 25 per cent higher rate of birth defects than the rest of the province, 1988-98. The JAG-commissioned Birth Outcomes Report finds more women miscarry in Sydney and Cape Breton County.

Yet it also says the rates of low birth weight and premature births were normal. Dr. Dodds says 10 per cent of birth defects can be linked to environmental factors. Dr. Jeff Scott, the province’s chief medical officer, says people cannot draw a link between abnormalities and the toxic waste sites.

FUTURE STUDIES

Dr. Guernsey plans to pursue funding to probe the health outcomes of all 28,000 workers employed at Sysco over a century.

She had copies of the employment records made in the 1990s and wants to determine what happened to each worker by following them through government cancer and other health databases.

Eventually, Dr. Guernsey wants to compare the workers’ stories to the health outcomes of their spouses - people who lived in the community and shared similar lifestyles but didn’t have the occupational exposure at Sysco.

The study would cost $200,000 a year for each of the first three years, she estimates.

2004: Gynecologists Dr. Henry Muggah and Dr. Bruce Wainman of McMaster University in Hamilton and researcher Helen Mersereau of the University College of Cape Breton began a four-year, $450,000 study on Sydney birth defects and stillbirths in October 2000.

Researchers will investigate the theory that toxins in the tar ponds and coke ovens sites, plus the stress of living next to them, may contribute to higher than normal rates of miscarriages and birth defects. Steps include voluntary blood testing of pregnant women to look for heavy metals and PCBs.

After the birth, a blood sample will be taken from the umbilical cord and a tissue sample from the placenta. Ms. Mersereau says researchers have telephoned 500 households asking about miscarriages and fertility problems..

Tuesday, February 26, 2002

Halifax Herald

Poisons in the soil

Chemicals taint the ground of all nine residential blocks around the coke ovens site

photo caption:

Francis Axworthy, in his Tupper Street home, suspects the 20 toxic substances found at elevated levels in his yard and basement are linked to his wife Ella's Alzheimer's disease, her two miscarriages and his daughter's death from cancer.

By Tera Camus / Cape Breton Bureau

Sydney - HIGH LEVELS of toxic substances have been found on every block of a Whitney Pier neighbourhood next to the government-owned coke ovens site, confidential documents show.

This newspaper has obtained details of the levels and locations of dozens of chemicals that were not released at a news conference in December, when government declared Sydney as safe as any other urban area of the province.

Documents show all nine blocks of Hankard, Laurier and Tupper streets, along with Frederick Street, Curry's Lane and sections of Lingan Road and Victoria Road, are contaminated by substances such as arsenic, lead, manganese, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fuel-based hydrocarbons such as the known carcinogen benzene.

Contaminants exceed either U.S. environmental standards for soil quality or guidelines of the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, set by scientists and policy-makers to protect people, animals and the ecosystem. Anything exceeding these standards are considered cause for further investigation.

Many of the chemicals found on the seven streets referred to in a December risk assessment by JDAC Environment as North of Coke Ovens, or NOCO, are also found beyond the chain-link fence that separates people from the hazardous coke-ovens site.

For more than a century, the ovens cooked coal to make coke, a fuel that fired the nearby Sydney Steel plant. Poisons produced in the process were released into the air as smoke, steam and dust, while other byproducts worked their way into the ground and water on the coke ovens site. Some contaminants came bubbling out of the ground on nearby Frederick Street.

Sydney's tar ponds, containing 700,000 tonnes of tarry toxic sludge, are one of the more visible legacies of the coking process. It's across from a Sobeys store and adjacent to the downtown area.

The largest government-funded study of the coke oven's nearest residential neighbours, done by JDAC Environment last summer, was released Dec. 4.

JDAC took random samples and tested properties whose owners volunteered to participate.

It recommended a half-metre of soil be removed from 60 properties in NOCO and 11 elsewhere in Sydney because of potentially elevated risk of cancer or other ailments. "The remedial actions . . . will result in a removal of the unacceptable conditions at those specific sites," JDAC wrote.

Provincial and federal officials have told individual residents what was found on their properties, but have not released a complete list of the levels and types of chemicals encountered to the community at large.

In December, an executive summary was issued, focusing on lead and arsenic - which have been identified as the primary hazards. Properties are coded to protect privacy and each is flagged for required cleanup action, if any.

This newspaper has obtained documents matching those codes to the property owners and addresses, allowing us to show what chemicals were found where.

That listing is published in today's edition (See Street-by-Street Test Results, next page.) Names of homeowners and their addresses won't be shown, to preserve residents' privacy. But the results have been organized street by street to give a better idea of where contamination levels are highest.

The reports and codes show 116 of 178 properties tested are recommended for soil removal due to potential increased health risks to the hundreds of adults and children who live or play on it. There are more than 200 properties in NOCO, according to the provincial property records database; most are vacant lots.

Of the 116 sites recommended for cleanup, 105 are on NOCO's seven streets and 11 other properties are elsewhere in Sydney - around the tar ponds or coke ovens, or deeper in Whitney Pier.

JDAC scientist Stephen Esposito said the number of properties that have tainted soil is higher than the total reported in December, because some were lumped together in the study. "We were trying to reduce the actual number of risk assessments we did," he said in a recent interview.

Most properties merged into single risk assessments were vacant lots, he said. On Frederick Street, properties bought for $1.2 million from worried homeowners by the province in 1999 after arsenic and other chemicals began seeping into backyards and basements were counted as one.

Some structures, such as four provincially owned regional housing duplexes on Hankard Street, were grouped under one risk assessment for excessive lead, total petroleum hydrocarbons, copper and manganese found in basement sumps.

JDAC recommended basements be cleaned and fixed.

Some structures such as St. Phillip's African Orthodox Church, where the West Indian Caribbean Festival is held each summer, were found to have excessive chemicals in their yards. Because no one lives there, the risk of exposure is dramatically reduced, so the soil can stay, Mr. Esposito said.

That's why dozens of vacant lots or common areas won't be cleaned up. But 25 properties can't be built on without more study, JDAC's report says.

The backyard of a home at the corner of Frederick and Lingan, used by JDAC as a satellite office, has enough arsenic, lead and total petroleum hydrocarbons in its soil to prompt the company to recommend it be taken away.

The nearby government-owned Joint Action Group office on Curry's Lane is getting the same treatment, because there is too much lead and arsenic in the soil. JAG is the government-citizen body created to give advice on tackling the cleanup of the coke ovens and tar ponds.

Francis Axworthy of Tupper Street, who lives near those two buildings, suspects the toxic substances found in his yard and basement are linked to his wife Ella's newly diagnosed Alzheimer's disease, her two miscarriages after they moved in 40 years ago and his 42-year-old daughter's cancer death.

Their daughter lived most of her life in their home before moving into her own place a few streets away, just outside NOCO.

"The study shows that remedial action is recommended on your property because (of the) possibility of health risks from exposure to arsenic, manganese, TPH (total petroleum hydrocarbons) and lead are above the levels considered acceptable by Canadian regulatory agencies and slightly above the levels in a typical Canadian urban environment," says the Axworthys' private risk assessment.

Residents whose properties were tested got detailed risk assessments that were not made public.

"Remedial action is being recommended to remove any possibility that someone could become ill as a result of exposure to the soils or water at the property."

Every property owner's risk assessment in which JDAC recommends soil removal includes the potential increased risks of cancer and other health problems for adults and children.

Any number above one means there's a slight theoretical increase in risk of adverse health effects, Mr. Esposito says.

JDAC's full study says that a theoretical risk doesn't mean there is an actual risk that people will die or get sick. That's because certain assumptions were made before samples were collected - one being that a person eating, inhaling or handling contaminants does so daily, around the clock, for over 70 years.

"The potential to overestimate risk in this study ranges from perhaps a low of 100 times to a possible high of roughly 100,000 times," the JDAC report says.

The report compared the potential dose for each person to the dose considered safe. Anything above one represents a potential health risk. The number for residents of the Hankard St. duplexes is 596.

Dr. Jeff Scott, the province's chief medical officer, says given the overestimation factor people should be safe to live in the NOCO area for the rest of their lives, even if soil is not removed.

"I'm very comfortable that the potential health risks for exposure to chemicals is very low," Dr. Scott said before Christmas.

The province and Ottawa now plan to spend $2.5 million to remove soil from yards tested, says Parker Donham, spokesman for the province's Sydney Tar Ponds Agency. Meanwhile, the agency is finding out what residents with tainted soil want done.

That's little comfort to the Axworthys, who have lived in their home since the 1960s. They have unacceptable levels of 20 chemicals in their yard and basement. Their risk assessment examines possible exposure to six.

Arsenic in their soil averages 94 milligrams per kilogram, more than eight times the Canadian guideline. That contributes to a potential increased risk for cancer of 294 in 100,000.

Others have much lower numbers for elevated potential cancer risk. Most are below 100, with a few at the extremes - 1.1 on the low end to as much as 2,303 for a family on Hankard Street who have elevated levels of the carcinogen chromium on their soil.

JDAC was not asked to look at:

- Prior exposures to soil and water

- The effects of heavy airborne pollution until 1988, when the biggest coal burner in town was permanently extinguished

- The cumulative effect of chemicals on smokers or others who are at higher risk of disease

- The sources of widespread contamination on residential land.

"The community should be concerned" about potential health risks, said Marcia Maguire, an occupational and public health professor at Toronto's Ryerson Polytechnic University.

Midway down Tupper Street, lead levels in soil range from 333 to 1,358 mg/kg. The national guideline is 140. Arsenic on the street ranges from an average of 47 to 125 mg/kg per property. The guideline for arsenic is 12.

Homes on Laurier Street near Victoria Road have levels of total petroleum hydrocarbons (which include the carcinogen benzene) above 7,000 mg/kg. So do houses three blocks down the street, near a popular blueberry field. The acceptable provincial limit is 750.

Government says it intends to hire a researcher to study the risk of eating blueberries grown in tainted soil.

Over on Frederick Street, one property whose owner didn't take a provincial buyout in 1999 had lead levels above 13,000. But Ms. Maguire said that doesn't necessarily mean there's a danger.

"It is possible that you can be sitting on contaminated land, but if that chemical is locked into soil (and if) you're not coming into contact (or) it's not getting into your air or the water or in the plants you are growing in your backyard, then you may never be exposed." Even so, "any dose can cause cancer," she said.

A researcher at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. is starting a voluntary testing program for pregnant women in industrial Cape Breton. Dr. Henry Muggah will examine blood and tissue for heavy metals and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs.

The Axworthys are both worried and skeptical.

"I don't think we're being told the truth," the elder Mr. Axworthy said in the kitchen, taking a long puff of his cigarette. "We're all going to die here with cancer, anyway."

His son Len wants the stress to end, especially for his parents.

"They should be relocated; make them feel better," he said. "They don't enjoy it here anymore."

Health officials have said that government doesn't plan to do any more soil testing in the NOCO area because it is safe.

One homeowner, Marcia Green, who refused to let government test her property, isn't clamouring to have it done now.

"If you have hot spots all around your property, it's not going to stop at a fence. It's here."

JDAC looked primarily at the area just north of the coke ovens but also gathered data from sites as far as 20 kilometres from the tar ponds and coke ovens.

Much of that material, particularly from testing outside NOCO, has yet to be released..

Tuesday, February 26, 2002

Halifax Herald

How safe is the Pier?

Scientists and environmentalists still can’t agree if health is at risk

Chemical threats to health

These chemicals can have detrimental health effects which vary according to exposure, the amount of chemical involved and the individual. The following is a list of toxic substances and their potential effects:

- Acenaphthene: liver function

- Arsenic: skin or lung cancer, skin lesions

- Antimony: blood glucose levels

- Benzene: leukemia

- Benzo(a)pyrene: cancer

- Beryllium: lung cancer

- Cadmium: kidney function, respiratory cancer

- Chromium: respiratory tract cancer

- Chrysene: cancer

- Cobalt: complicates kidney problems

- Dibenz(a,h)anthracene: cancer

- Ethylbenzene: liver and kidney damage, developmental problems

- Fluoranthene: kidney function

- Indeno(1,2,3)pyrene: cancer Lead: impairs brain development, memory

- Manganese: central nervous system damage

- Mercury: hand tremors

- Molybdenum: uric acid in blood

- Naphthalene: weight loss, nasal hyperplasia

- Nickel: reproductive system damage

- Pyrene: kidney function

- Selenium: selenosis (silver discolouration of skin)

- Thallium: liver damage

- Toluene: liver and kidney damage, neurological problems

- Vanadium: decreased hair cystine levels

- Xylenes: liver and kidney damage, developmental problems

- Zinc: weight problems

Source: JDAC Environment, Nov. 7, 2001

By Paul Schneidereit / Staff Reporter

Is it safe to live in Whitney Pier?

Government-paid scientists and health officials say yes. Environmentalists say no.

“I’d have no concern living there, now and into the future,” says Ron Brecher, one of the scientists hired to peer-review the chronic health risk assessment of the Sydney area north of the coke ovens, known as NOCO, done by JDAC Environment.

That report, released in December, recommended cleaning up dozens of properties in the neighbourhood but only after vastly overestimating the potential health risks from contaminants, said Mr. Brecher, a toxicologist with GlobalTox International Consultants.

He called the NOCO study well done. “Risk assessments are, by their nature, intended to overpredict rather than underpredict risk,” Mr. Brecher said from Guelph, Ont.

“The real goal is that it not miss risks that might be there.”

Based on this conservative approach, the JDAC study recomended action to reduce potential human health risks but added the biological testing done last summer found “no empirical evidence in the community that the population is currently being exposed to levels that would cause health concerns.”

“The blood testing (last summer) was sort of a reality check,” Mr. Brecher said. “It came back very similar to other communities that don’t live by the Sydney tar ponds.”

Last summer, more than 370 Sydney adults and children had their blood tested for lead and their urine for arsenic. Two adults tested positive for excessive lead, and 15 people, including 11 toddlers and teens, had elevated arsenic levels. Medical officials called those findings consistent with levels found in other areas.

The study compared the Sydney results to those from three communities in Ontario and populations in Sweden, Germany and the United States.

But Daniel Green, a scientific adviser to the Sierra Club of Canada, rejects the notion the Sydney neighbourhood is safe.

“It’s mind-boggling to try to understand why Health Canada-hired scientists are minimizing this contamination event,” said Mr. Green, a masters student in neurotoxicology at the Universite du Quebec in Montreal.

The biological testing last summer was far from reassuring, he said. Many kids who had previously tested high for arsenic were sent to live with relatives or forbidden to play in the dirt, so it’s not surprising that followup tests found contamination had dropped to safe levels, he said.

Nova Scotia’s chief medical officer, Dr. Jeff Scott, acknowledges that levels may have come down due to those factors. But there are other possible reasons the first results were higher, he said. Urine tests were done in the morning, when arsenic could be more concentrated. The followup tests, which found that only two of the original 15 people still had unacceptable levels, used composite urine samples collected over 24 hours.

Dr. Scott’s staff have since looked at whether people who had high levels of lead and arsenic in their bodies also had high levels on their properties. “There’s no correlation,” Dr. Scott said.

But Mr. Green is convinced soil contamination is affecting residents’ health. Exactly how it gets into the body remains unclear, he said.

Meanwhile, he called the NOCO-area risk assessment a “mathematical exercise” that could be manipulated by plugging in different values to get different results. He said he doubts the study’s claim that the report’s conclusions overestimated the risks.

For example, the study’s authors assumed that toddlers would consume 80 milligrams of soil a day. But, Mr. Green said, the authors could have easily used one gram (1,000 milligrams) or even five grams of soil a day, which would have increased potential risk.

Bryan Leece, a toxicologist who worked on the study for the JDAC consortium, called Mr. Green’s arguments “not scientifically sound.”

Children who ingest up to five grams of soil in a day are believed to suffer from a medical disorder, he said. U.S. risk assessments use a figure of 100 milligrams of soil a day, based on the southern U.S. being snow-free year-round.

More criticism of the NOCO study has come from Sierra Club scientist James Argo, a medical geographer, chemist and exposure assessment professional.

In a Jan. 22 letter to Sydney pediatrician Dr. Andrew Lynk - a copy of which was released by Mr. Green - Mr. Argo, a former Health Canada scientist who runs IntraAmericas Centre for Environment and Health, wrote that the study is flawed in three significant ways: it uses an adult body weight that ignores women; its data distribution models may underestimate risk; and North Sydney, the area chosen to compare to Whitney Pier, is probably contaminated.

Mr. Leece said he “absolutely” rejects those arguments. He said the report’s authors blended the body weights of all age groups, which covered women; data distribution models were verified by statisticians; and North Sydney was chosen because it was a similar urban area with similar geology and little or no heavy industry.

“I think that perhaps some of these questions are coming out of a lack of experience in the toxicology and the risk assessment process,” said Mr. Leece, who has a doctorate in biochemistry/toxicology.

“The basic concept is very simple. Is it there, how much is there, does it get into people and does that pose a risk? But in order to get there, there’s an awful lot of underlying science that needs to go on.”

Mr. Green said he has more than 15 years’ experience in studying hazardous wastes.

“I think what one should look at is what is being said by a person, not necessarily the number of degrees after the person’s name.”

Richard Lewis is an environmental engineer in Florida. He said last spring that Whitney Pier children should not play in the dirt because of high levels of lead and arsenic found in limited sampling of the soil in the area. His concerns led to both the biological and chronic risk studies.

Mr. Lewis now says his concerns have been addressed.

“We didn’t have any samples from people’s backyards,” he said by phone from Fort Myers, Fla. “Not that we knew there was something wrong.

“Now, I feel like we have sufficient data to be able to make the decisions that are currently being made.”

Mr. Lewis acknowledged he’s looked at the NOCO study but not the individual test results. Asked if he’d now let his children play in the Whitney Pier dirt, he said he’d want to review the data before making such a decision.

But, he added, “I have a great deal of respect for Ron Brecher. I would trust his opinion.”

The NOCO study took random samples from different parts of each property and also tested areas likely to be contaminated, such as ash piles and basement sumps.

Contaminants were found in both random samples and suspected hot spots at levels that triggered recommendations for cleanup, Mr. Leece said.

“I don’t think that it’s fair to say that the study can be used to pinpoint individual problems that say, ‘Well, this is self-induced.’ “

Finding the source of contamination was not in their mandate, he said.

“It may have been as a result of fallout from the coke oven operations. It could have come from a number of sources.”

The study also could not predict what might be found on untested properties. But Mr. Leece is confident it’s safe to live in the community.

“We all accept a certain amount of risk by living in an urban area,” said Mr. Leece, who works in metro Toronto. “The real question is, how much different am I living next to the coke ovens than I would have been living in any other part of an urban community.

“(The answer is) it’s not hugely different than an awful lot of other communities.”

Mr. Leece also said the study couldn’t calculate potential risks for people whose health may already be affected by prior exposure to chemicals.

“(But) the contributions from current exposures are unlikely to have a significant effect on health status for members of the community, regardless of their current state.”

Dr. Lynk says he’s not worried that his son has played soccer and baseball on the dirt in Whitney Pier.

The risk may not be zero, “but it’s pretty darn small,” he said.

He’s looking into the concerns of the Sierra Club, which he says fills an important role of providing checks and balances. But he says it’s unlikely there’s a significant problem.

John Malcom, CEO of the Cape Breton district health authority, says stress and the loss of potential jobs from employers who won’t move into the greater Sydney area are important reasons why, “for the health of this community, we need to put this behind us and clean it up.”

But, Mr. Malcom added, people should realize there are other pressing health challenges in Cape Breton, including lifestyle choices like nutrition and smoking, the economy and education.

“The single largest environmental risk Cape Bretoners still face is walking into a smoky bingo hall,” he said..

The Sydney Tar Ponds - Excerpts from news reports.

Note: The Sierra Club of Canada is not responsible for the content of the following reports nor affiliated with its authors.

September 14, 2002

The Toronto Star

Stink growing near Sydney pond

Residents denied toxic cleanup unless they waive litigation

WHAT THE federal and provincial governments are doing in Whitney Pier is just plain nuts.

Either officials are deliberately ignoring a serious health hazard facing hundreds of men, women and children, or they are wasting $2 million on a public relations exercise that is not making anyone feel better about anything.

You decide which.

Here are the facts:

- The governments are spending $2 million to clean up a few dozen homes and yards in one Sydney, N.S., neighbourhood near a defunct steel mill and toxic waste site.

- It is almost certain that many other homes in Whitney Pier are also contaminated, but officials have refused all further testing. Even where a home is surrounded by poisoned soil, the government won’t test or offer to clean it up.

- Officials have refused to test any homes in the other two neighbourhoods that surround the old steel mill site, even though private tests have found similar poisons in one of them.

- The governments have agreed to clean up 63 homes ÷ but only if residents sign away their right to sue if the job isn’t done right.

Sydney is the home of what Sierra Club of Canada president Elizabeth May calls the worst toxic waste site in Canada. It’s an impossible claim to verify, but the obvious truth is that the problem is very bad. The tar pond’s stinking waters shelter at least 40,000 tonnes of cancer-causing PCBs and all of Sydney’s raw sewage.

A field just above the pond is saturated with chemicals and metals like benzene, toluene, arsenic and lead. When an activist started shovelling the muck into barrels as a publicity stunt, one reporter covering the event passed out. Another threw up.

No one disputes the pond is unpleasant. What they do argue about is whether the stinking poisons hurt people. Sydney has some of the worst health statistics in Canada. Birth defects are high, lifespans are short. The rates of some cancers and other diseases lead the nation.

The official line has been that the pollution and the sickness are not related, that most of the problems can be explained away through local lifestyle issues connected to poverty, smoking and diet. That argument drives May crazy.

“It’s absurd that the government position is that whatever is wrong with this community is not related to the fact they are living in the midst of toxic waste,” she says.

Both provincial and federal officials have made key decisions in this mess. Working through a complex spider web of committees and consultants, the two levels of government are sharing the bill for the debacle, and calling the shots.

Four years ago, a mother living on Whitney Pier’s Frederick St. started to worry about the goo in her basement. The goo was tested. It turned out to be full of arsenic. Frederick St. residents kicked up a fuss and, with an election looming, the provincial government agreed to buy them out.

That started the neighbours wondering. People who had lived in the shadow of the steel plant for generations, people who had scoffed at the alarmed residents of Frederick St., now demanded their own properties be tested. The government did what governments do in a crisis ÷ it hired a consultant.

After the first tests came back, the Florida scientist hired to study Whitney Pier warned people not to let their children play outside until further study was completed. Empty lots where children had frolicked were fenced off with bright red plastic webbing because arsenic and lead were found in the soil.

Now residents were downright panicked, determined to get themselves and their children away from the poisons they suspected might be causing some of Sydney’s horrible health problems. When the government offered more testing, many refused, afraid that the government would use the results as an excuse not to move them.

In the end, the owners of only 124 properties agreed to the testing. When the tests were done, consultants recommended 88 properties be cleaned up, including 63 private homes.

Even then, there was a catch.

The authorities insisted property owners promise not to sue in connection with the cleanup.

The way the Rev. Vincent Waterman sees it, they want him to barter away the health of future children in exchange for his own peace of mind. Waterman doesn’t know the exact nature of the poison in the basement of his church rectory, but he knows it must be bad because government workers bolted a big steel plate over the mess and told him not to go near it.

He wants to sign the cleanup contract, but is afraid. What if they don’t get all the poison and a child ends up playing in that basement after he moves or dies? What if they find more toxins after the first cleanup is finished?

“It’s ludicrous to agree not to sue before the work has even begun,” he says.

“You don’t want a child in the future stuck because of a clause that an adult signed unwisely. I am truly caught between the devil and the deep blue sea. I wouldn’t want a dog to be in my predicament.”

In the meantime, the Sierra Club has launched its own testing, a dust survey to see if the poisons are migrating inside homes.

Parker Bars Donham is the government spokesperson for the project. He has already dismissed the Sierra Club study as “propaganda.”

When asked why the government is cleaning up the properties, Donham first cites “health concerns” identified by the consultants. But when asked why the government won’t test adjoining properties, if there are health concerns, he backtracks.

“Our conclusion is that there isn’t cause for alarm about people’s health,” he says.

So why are they spending $2 million to clean it up?

“As a matter of public health, we don’t think it’s absolutely necessary,” he says. “We are cleaning up to fulfill a political commitment to the people of this community.”

Maybe that is supposed to be reassuring, but somehow, it isn’t.

“I’m at an age when I will have to go under ground soon anyway,” says Waterman, who just turned 76.

“I’m left in limbo. I guess I must just live with this. I’m in more hot water than a tea bag.”

Monday, March 11, 2002

Halifax Herald

C.B. pollution standards spur demand for data

By Tera Camus / Cape Breton Bureau

Sydney - The Sierra Club of Canada demanded Friday that the federal government release all data that led to Ottawa creating a lower standard for cleanup for toxic land in Sydney than in other cities across Canada.

The environmental group says Health Canada is ignoring scientifically tested safe soil guidelines established by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Instead, the government is using land in North Sydney as a benchmark.

The CCME limit for arsenic in soil is 12 milligrams of arsenic per kilogram of dirt. The federal government's limit for Sydney is 72 mg/kg.

"It seems every time Health Canada finds high contamination levels on a property, they change the standard to make what was unacceptable yesterday, acceptable today," said Daniel Green, scientific adviser to the Sierra Club.

The federal Health Department refused last week to disclose results from tests taken last summer in Sydney. But spokesman Don Ferguson said most of the soil samples from Sydney fared better than those taken from North Sydney. He refused to how many soil samples tested below the lower CCME limits.

Thursday, March 7, 2002

Halifax Herald

Sydney soil tests find most homes safe

By Tera Camus / Cape Breton Bureau

Sydney - Government officials say that only one soil sample from among 333 tested last summer in Sydney and nearby communities showed an unsafe concentration of toxins.

Health Canada spokeswoman Tracy Taweel described the results as consistent with earlier health studies that declared the communities around the infamous tar ponds and coke ovens sites to be safe.

“There was nothing in there that gave cause for further alarm,” Ms. Taweel said. But Raylene Williams is far from convinced. Her Intercolonial Street property, on the shore of the tar ponds, tested cleaner than those in North Sydney, 10 kilometres away.

“Look, I’m confused, I’m really confused,” Ms. Williams said as she flipped through the pages of test results at her kitchen table, where the window overlooks the 700,000 tonnes of toxic goo in the tar ponds.

“This is tearing me apart, it’s taken over my life,” she said. “The government is, after lying to us so damn much. . . . I’m 60 years old right now and I feel that everything I’ve worked for is worthless. I can’t sell my property, I can’t enjoy my property.”

More worrisome now is the health of her grandchild, just over a year old. His mother has high levels of lead in her breast milk.

“There’s something wrong with his leg and it’s affecting his motor skills, and the doctors are blaming it on his mother’s milk,” Ms. Williams said.

Ms. Williams’ soil was tested for 49 chemicals, many of them known carcinogens or having the potential to impair bodily functions. Forty of the 49 were found to be less concentrated than in North Sydney properties but many were still well above national guidelines for safe soil established by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment.

Ms. Williams doesn’t believe the latest findings because they differ from those resulting from tests done at the Environmental Services Laboratory last summer through Mayor John Morgan’s office.

Those samples tested seven times above acceptable limits for arsenic and three times higher for lead, iron and manganese. The results issued Wednesday showed three times the acceptable level of arsenic, twice the acceptable level of lead and slightly more than the acceptable limit of iron.

In North Sydney, arsenic levels averaged 72 milligrams per kilogram of soil - the national guideline is 12 - while lead was twice as high as the acceptable limit of 140 mg/kg. Other chemicals among 90 samples taken from downtown North Sydney also exceeded national numbers.

Federal and provincial government officials refused Wednesday to disclose any of the concentration levels found in Sydney.

“We won’t do that,” said Don Ferguson, director general of Health Canada, saying it’s to protect the interests of property owners.

He said most soil samples taken in Sydney produced better test results than those in North Sydney but he refused to say how many were over the national guidelines for safe soil.

One property showed lead at more than 1,400 mg/kg. Mr. Ferguson refused to say where that property is but he said it will be investigated further.

He said government officials picked North Sydney for comparison testing because it is an urban area not believed to be affected by fallout from the government’s coking process at Sydney Steel that turned the sky orange with uncontrolled pollution for decades.

North Sydney is 10 kilometres downwind of Sydney. Nearby Sydney Mines also had a steel plant for years.

“There were no patterns,” Mr. Ferguson said of the results. “If there was a pattern, it was random (levels) were up and down.

“If we did the whole province of Nova Scotia, I don’t think we’d find anything different.”

He also reiterated that the federal and provincial governments will not clean up any property that tests similarly to North Sydney samples, even if it exceeds Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment values.

Contamination levels in North Sydney are considered naturally occurring, Mr. Ferguson said.

“You can’t beat Mom Nature,” he said. “You choose to live in an urban centre, you choose to live in those conditions.”

Many area residents have demanded to be moved at government expense and have said that national environmental standards should be applied to the area.

Friday, March 1, 2002

Halifax Herald

Studies numerous as the opinions

Sydney residents suffer higher rates of cancer and other illnesses. Is their environment to blame?

Photo caption (file): Elizabeth May, of the Sierra Club of Canada, went on a hunger strike on Parliament Hill in Ottawa last May to protest the government’s lack of action on Sydney’s toxic waste problem.

By Susan LeBlanc / Staff Reporter

OVER THE PAST 25 years, a number of major health studies have been done on the Sydney area:

March 1977: Health and Welfare Canada reports that the testing of hundreds of Sydney schoolchildren in 1976 found “a small but statistically significant connection” between their respiratory function and the level of air pollution in their neighbourhoods. But “there was no evidence that this resulted in disease as judged by ear, nose and throat examinations,” says the report. Sydney adults tested normally.

December 1985: Dr. Yang Mao of Health and Welfare Canada says death certificates from 1971 to 1983 show Sydney residents suffered “significantly elevated mortality” from cancer. Men aged 35 to 69 were especially prone to cancers of the stomach, digestive tract and lungs. Women died mostly from cancers of the stomach, breast, uterus and cervix.

The study also finds high death rates from circulatory diseases and, among men, deaths from respiratory illnesses, cirrhosis and pneumoconioses (lung diseases, including black lung). The report notes stomach cancer and some respiratory diseases have been linked generally to coal mining; lung cancer has been tied to coke oven workers.

“Effects (of related contaminants) to the general public at normal ambient air levels have not been demonstrated,” it says.

August 1998: Cantox Environmental of Halifax releases a study prepared for the provincial Health Department on the human health risk of the Frederick Street area in Sydney. (Residents had grown concerned when liquid oozed from a nearby rail bed and when coal cleanup at the nearby coke ovens site appeared to raise irritating dust.)

Researchers used a computer model to assess risk, combining data on area contaminants, their potential hazards and residents’ estimated daily exposure. Residents’ blood and hair samples were analysed, as were soil, drinking water from nine homes and root vegetables from local gardens.

While lifelong exposures to carcinogenic PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) were “slightly elevated,” overall “no measurable adverse health effects in local residents are predicted to result from long-term exposure to chemicals in the Frederick Street neighbourhood,” Cantox says.

September 1998: A report by Health Canada scientists Dr. Pierre Band and Dr. Michel Camus reveals Sydney residents have much higher death rates from 22 diseases than other Canadians do. Death by cancer is 16 per cent higher in Sydney, says the report, done for the Joint Action Group.

From 1951 to ‘94, residents’ lifespans were 10 years shorter than could be expected. Among the top killers: cancers of the esophagus, lung, stomach, breast, pancreas and bone marrow. Non-cancer killers included asthma, diabetes and multiple sclerosis. It’s suggested colon and breast cancer, plus male diabetes, get a further look.

October 1998: Dr. Judy Guernsey of Dalhousie University in Halifax and other researchers find Sydney-area men and women much more likely to develop cancer than other Nova Scotians. Females were 47 per cent more apt to get cancer in the period 1989-1995, while males were 45 per cent more likely.

“Women were at increased risk for cancers of the breast and cervix, and Sydney men were at increased risk for cancers of the colon and rectum and prostate, relative to N.S. women and men,” the researchers say. They also find that residents of other parts of Cape Breton County were more at risk, especially for cancers of the stomach, breast and cervix for women and stomach, lungs and prostate for men.

January 1999: A review of the 1998 Cantox study by Ontario researchers on behalf of the Sierra Club environmental group disputes Cantox’s claim that Frederick Street residents are not at risk. “We are unable to support (the conclusion) based on the meagre sampling data and the uncertainties contained in the methodologies employed,” the review says.

April 1999: Three Ontario doctors commissioned by Cancer Care Nova Scotia review the two 1998 studies and find no “specific cancer problem, but rather an overall health problem” in Cape Breton. The panel agrees with Health Canada that since the 1950s, Cape Bretoners have been more apt to die of cancer and other diseases than other Canadians have been. But the experts blame lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity, not the environment.

Fall 2001: An updated 1999 study by Dr. Linda Dodds of Dalhousie University says Sydney had a 25 per cent higher rate of birth defects than the rest of the province, 1988-98. The JAG-commissioned Birth Outcomes Report finds more women miscarry in Sydney and Cape Breton County.

Yet it also says the rates of low birth weight and premature births were normal. Dr. Dodds says 10 per cent of birth defects can be linked to environmental factors. Dr. Jeff Scott, the province’s chief medical officer, says people cannot draw a link between abnormalities and the toxic waste sites.

FUTURE STUDIES

Dr. Guernsey plans to pursue funding to probe the health outcomes of all 28,000 workers employed at Sysco over a century.

She had copies of the employment records made in the 1990s and wants to determine what happened to each worker by following them through government cancer and other health databases.

Eventually, Dr. Guernsey wants to compare the workers’ stories to the health outcomes of their spouses - people who lived in the community and shared similar lifestyles but didn’t have the occupational exposure at Sysco.

The study would cost $200,000 a year for each of the first three years, she estimates.

2004: Gynecologists Dr. Henry Muggah and Dr. Bruce Wainman of McMaster University in Hamilton and researcher Helen Mersereau of the University College of Cape Breton began a four-year, $450,000 study on Sydney birth defects and stillbirths in October 2000.

Researchers will investigate the theory that toxins in the tar ponds and coke ovens sites, plus the stress of living next to them, may contribute to higher than normal rates of miscarriages and birth defects. Steps include voluntary blood testing of pregnant women to look for heavy metals and PCBs.

After the birth, a blood sample will be taken from the umbilical cord and a tissue sample from the placenta. Ms. Mersereau says researchers have telephoned 500 households asking about miscarriages and fertility problems..

Tuesday, February 26, 2002

Halifax Herald

Poisons in the soil

Chemicals taint the ground of all nine residential blocks around the coke ovens site

photo caption:

Francis Axworthy, in his Tupper Street home, suspects the 20 toxic substances found at elevated levels in his yard and basement are linked to his wife Ella's Alzheimer's disease, her two miscarriages and his daughter's death from cancer.

By Tera Camus / Cape Breton Bureau

Sydney - HIGH LEVELS of toxic substances have been found on every block of a Whitney Pier neighbourhood next to the government-owned coke ovens site, confidential documents show.

This newspaper has obtained details of the levels and locations of dozens of chemicals that were not released at a news conference in December, when government declared Sydney as safe as any other urban area of the province.

Documents show all nine blocks of Hankard, Laurier and Tupper streets, along with Frederick Street, Curry's Lane and sections of Lingan Road and Victoria Road, are contaminated by substances such as arsenic, lead, manganese, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fuel-based hydrocarbons such as the known carcinogen benzene.

Contaminants exceed either U.S. environmental standards for soil quality or guidelines of the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, set by scientists and policy-makers to protect people, animals and the ecosystem. Anything exceeding these standards are considered cause for further investigation.

Many of the chemicals found on the seven streets referred to in a December risk assessment by JDAC Environment as North of Coke Ovens, or NOCO, are also found beyond the chain-link fence that separates people from the hazardous coke-ovens site.

For more than a century, the ovens cooked coal to make coke, a fuel that fired the nearby Sydney Steel plant. Poisons produced in the process were released into the air as smoke, steam and dust, while other byproducts worked their way into the ground and water on the coke ovens site. Some contaminants came bubbling out of the ground on nearby Frederick Street.

Sydney's tar ponds, containing 700,000 tonnes of tarry toxic sludge, are one of the more visible legacies of the coking process. It's across from a Sobeys store and adjacent to the downtown area.

The largest government-funded study of the coke oven's nearest residential neighbours, done by JDAC Environment last summer, was released Dec. 4.

JDAC took random samples and tested properties whose owners volunteered to participate.

It recommended a half-metre of soil be removed from 60 properties in NOCO and 11 elsewhere in Sydney because of potentially elevated risk of cancer or other ailments. "The remedial actions . . . will result in a removal of the unacceptable conditions at those specific sites," JDAC wrote.

Provincial and federal officials have told individual residents what was found on their properties, but have not released a complete list of the levels and types of chemicals encountered to the community at large.

In December, an executive summary was issued, focusing on lead and arsenic - which have been identified as the primary hazards. Properties are coded to protect privacy and each is flagged for required cleanup action, if any.

This newspaper has obtained documents matching those codes to the property owners and addresses, allowing us to show what chemicals were found where.

That listing is published in today's edition (See Street-by-Street Test Results, next page.) Names of homeowners and their addresses won't be shown, to preserve residents' privacy. But the results have been organized street by street to give a better idea of where contamination levels are highest.

The reports and codes show 116 of 178 properties tested are recommended for soil removal due to potential increased health risks to the hundreds of adults and children who live or play on it. There are more than 200 properties in NOCO, according to the provincial property records database; most are vacant lots.

Of the 116 sites recommended for cleanup, 105 are on NOCO's seven streets and 11 other properties are elsewhere in Sydney - around the tar ponds or coke ovens, or deeper in Whitney Pier.

JDAC scientist Stephen Esposito said the number of properties that have tainted soil is higher than the total reported in December, because some were lumped together in the study. "We were trying to reduce the actual number of risk assessments we did," he said in a recent interview.

Most properties merged into single risk assessments were vacant lots, he said. On Frederick Street, properties bought for $1.2 million from worried homeowners by the province in 1999 after arsenic and other chemicals began seeping into backyards and basements were counted as one.